|

The Zeppelin is Down by Raul Colon |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Home Page | Articles Index | ||

|

Captain Leefe Robinson | ||

|

Common knowledge states that a young British Royal Navy pilot, named Leefe Robinson, was the first flyer to shoot down one of the massive German Zeppelin dirigibles. Even today, some folks in England still recall the exploits of Robinson. He brought a dirigible down one foggy night and the Zeppelin fell down in a blaze near Cuffley, England. In the early days of the Great War, the German Zeppelins brought much terror to the residents of England. High level bombing runs made by formations of Zeppelins, sparked a strong anti-German sentiment among the British. They recalled the stories of H.G. Wells and other futuristic writers who predicted hell raining from above. Fortunately for the citizens of London at the time, this scenario would not become a reality until World War II.

The hydrogen filled Zeppelins could only carry a small bomb load and its bombing accuracy was nonexistent. Britain quickly adapted their defenses to meet the Zeppelin threat. Huge artillery pieces, for the first time were not pointed to land targets, but were instead pointed toward the skies. When a Zeppelin bombing run commenced, British gunners opened indiscriminate fire against them. Loses sustained by the German’s Zeppelin fleet were quickly becoming unsustainable. The Zeppelin changed tactics. They would now bomb from high above the clouds, sacrificing what little accuracy they could achieve in low-level bombing, for the safety of the dirigible and crew. Robinson downed the Zeppelin in 1915, but it was not officially recorded until September 3rd, 1916. In the mean time, another Royal Navy Air Service pilot, Reggie Warneford, destroyed a Zeppelin, the L.37, over Ghent, Belgium on June 7th, 1915. This act, over a nearly deserted town in a faraway land, brought Warneford nearly no recognition at home, whereas Robinson's kill was in clear skies near London with millions looking up—publicity was everything. Reginal Alexander John Warneford was the model British Empire solider of those days. He was born in the jewel of the Empire, India, and was schooled at the famous English Collage in Simla. He later left India for England where he continued his studies at Stratford-Avon Grammar School. After graduating at the top of his class, Warneford, who had displayed a particular impressive mechanical skill, particularly with engines, decided to join the Merchant Marine and was serving with the Indian Steam Navigation Company, when the Great War started on August 1914. He quickly resigned his commission and made his way to Great Britain, where he promptly joined the Second Battalion of the Sportsman Regiment—an infantry outfit. The combat training for the unit took more time than Warneford desired—he feared, as many others in the Imperial Army did at the time, that the War would be over quickly, and he might miss the chance to enter the fray. After a lot of thinking, he decided to transfer from Sportsman to the infant Royal Navy Air Service. His friends generally agreed that Reggie was a little too sure of himself, inclined to be boastful and brutally frank—not the best traits for a combat pilot. However, his instructors of the Navy Air Service, managed to curb his impetuosity somewhat. By the time he advanced to the prestigious Central Flying School at Upavon, he had proved himself to be a daring airman. |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

By May 1915, Reggie had won his RNAS wings and was transferred to the Number 2 Naval Squadron located at the Thames Estuary. After a brief time there, young Warneford was shipped across the English Channel to the Number 1 Naval Squadron under the command of Wing Commander Arthur Longmore, who would become an Air Chief Marshall during World War II. He was stationed at Dunkirk Air Base and was given an outdated Voisin scout biplane. After taking off on his first mission, Reggie and his observer spotted a German observation plane circling at low level over Zeebrugge. He immediately went in pursuit and ordered his observer to open fire from his light machine gun, but his gun was jammed after only firing a couple of rounds. However, Reggie still followed the German plane all the way back to their base. When he landed back at Dunkirk, Wing Commander Longmore, impressed by the report presented by Warneford, provided Reggie with a better aircraft, the high-winged monoplane Morane Parasol.

Young Warneford was sent off to do, what he was born to do—take the fight to the enemy, and more—from all accounts, he did just that. He chased enemy planes out of the skies in Northern France, attacked troop movements and made various bombing runs at German artillery emplacements. All of his exploits gave Reggie the reputation he craved, that of a young and daring pursuit pilot. During the wee hours of June 7th, Reggie got another opportunity to add to his already impressive record. The Admiralty warned Longmore command, that three Zeppelin dirigibles, that had been in Southern Britain, were on their way back to their home field sheds. Reggie’s Morane took to the air around 1:00 a.m. and quickly rose to 2,000 feet. Other aircraft were also dispatched to assist in the mission. About an hour into his flight, Reggie, already at 3,000 feet, began to look for his companions, he found no one. He promptly checked his compass to see if he had strayed from his flight plan, and began the search again. Promptly, two planes, both Moranes, appeared from the south to join Reggie in his run. During the long flight to Brussels, he sat in his cockpit wondering what a dirigible shed would look like from above at night. The three planes found their target without much difficulty. One of Reggie’s wingmen, an airman from Dublin, known only as Wilson, quickly commenced a bombing run. German ground fire was somewhat subdued. At first the gunners thought that the attacking British airplanes were actually their own, returning from a bombing mission. But soon they realized that the incoming planes were not theirs, and German searchlights filled the sky—Reggie and his fellow airmen were promptly under heavy anti-aircraft fire. Nevertheless, they continued with their mission and on their two bombing runs, they manage to destroy one shed and heavily damage a brand new dirigible on the ground, marked L38. |

|

Morane Parasol L Type |

|

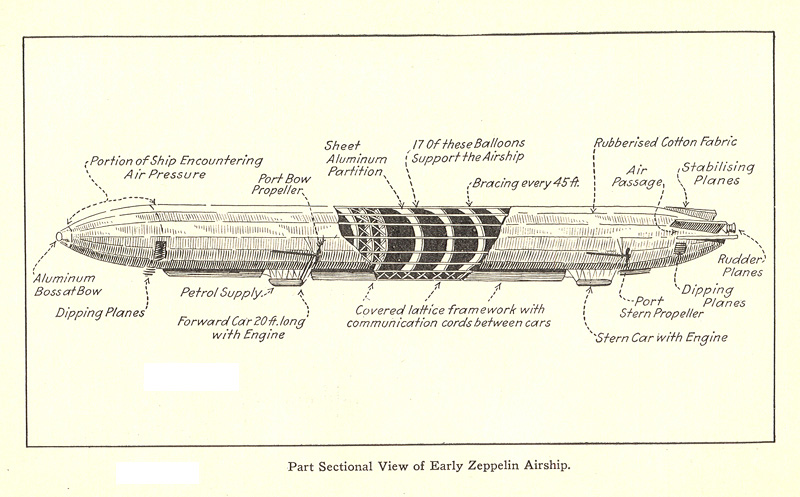

The mission was not over, there were two additional German Zeppelins circling the German shed base, the L39 and L37, and Reggie’s party needed to confront them. The dirigible designated L37 was 521 feet long and her main eighteen gas ballonets carried 953,000 cubic feet of hydrogen. She had four 210 hp Maybach engines. It was manned by a complement of twenty-eight officers and crewmen. The L37 had an impressive defensive armament for the times; it carried four heavy machine gun posts, located in the engine gondolas. These positions provided the gunner with a clear firing view and an effective range finder from both sides of the airship. No forward gun was mounted anywhere along the upper side of the dirigible. After the two bomb runs, Warneford stared in amazement as he realize that what he had in his sights was actually an airborne German Zeppelin!

He was stunned at the sight; the Zeppelin was just a half a mile away and closing fast. Suddenly the big dirigible opened fire from its four machine guns, and slugs from the airship plunged big holes through the frail wing of the Morane Parasol No. 3253. Puzzled by the suddenness of the attack, Reggie banked his aircraft to the left in order to avoid more incoming fire. It should also be mentioned that Reggie’s Morane model did not carry a machine gun. The fog that permeated the skies was vanishing fast—in just a few minutes, German artillery and airplanes would be able to clearly spot the attacking British planes—if something was to be done, this was the time to do it. Warneford, after watching the dirigible turning a hard right turn, thought that the airship was headed towards Ghent, but suddenly, the Zeppelin changed direction, and was now headed toward Reggie’s group. Two more bursts of fire came from the forward gondolas. The RNAS pilot gave the Morane the ride of its life and tried to climb as fast as possible, but the massive amount of crisscrossing fire scuttled the idea, and Reggie went in to a full dive instead. He studied the situation for just a few seconds and decided that this was the moment, the moment in one’s life that would be defined. He could have peeled off to the east and crossed back to the safety of the French lines, but he choose to come back, to re-engage the enemy dirigible and try to take it out of the air. Carrying only six, twenty pond bombs in a rudimentary rack toggle and wire design, Warneford went back at the Zeppelin. He made several passes to the starboard side of the airship, and every time he was discouraged from further action by the persistent German gunners in the right side gondolas. |

|

| Zeppelin Crew |

|

Lieutenant Von der Heagen, the senior officer aboard the L37, gave its crew the order to climb as fast as possible in order to reach a low cloud concentration three minutes away. After reaching the cloud cover, Heagen directed the huge ship once again toward Ghent. Although he knew he was out gunned and probably outclassed by the Zeppelin, Reggie refused to let the chase die. After several minutes of continuing failures in the part of Reggie’s Morane, to achieve attitude parity with the L37, Warneford was caught completely by surprise when the Zeppelin started a quick dive out of the 7,000 foot cloud layer that served as its cover. It was unmistakable; the Zeppelin was headed toward its shed at Ghent. By this time, Reggie had managed to steer his plane above the L37 and was in a position to use his remaining six bombs on it.

Again Warneford was astonished at the size of this air monster, he was sure, if he tried, he could have landed his aircraft on its topside. Below lay the small village of Ghent. Reggie’s Morane dove down straight for a 500 foot long upper panel at the top of the Zeppelin. He began to pull his bomb toggle, “One…two…three!” he counted. He felt the bombs drop from its rack and he fully expected them to explode immediately after contact with this leviathan. “Four…five…”, he continued to count, and then a blinding explosion shook the upper section of the Morane wings. The explosion was so spectacular that Reggie needed to turn his Morane with violence, a maneuver that if it was not for his seatbelt, it would have kicked him from his cockpit. He gasped at the situation and rammed his stick forward in order to force the airplane into a steep dive. Chunks of burning framework hurtled all over the sky. He was engulfed in a debris field so large that the entire sky seemed to be on fire. Over the next few minutes Warneford’s plane was absorbed in flying clear of the debris, getting himself back on an even keel, and desperately trying to adjust his air and gas mixture to dampen out a series of pops from his Le Rhone engine. Below, the remains of the huge L37 fell completely out of the air on the historic Convent of St. Elizabeth in the Mont Saint Armand suburb of Ghent. One man on the ground was killed and several more severely injured. Miraculously, the helmsman of the Zeppelin survived the crash unharmed. He was the only man among the doomed crew of the L37 to survive. He later retired from the German Air Service and opened a small beer hall, where he related the story of his encounter with the British for years to come. Back in the skies over Ghent, Reggie, after noticing that his Le Rhone engine started to respond somewhat, he finally regained a measure of control on his Morane and brought it back to level flight, but for the most part, he was gliding his plane down. He took a look down at the convent to see for the first time what he had done. It was an amazing view, the remains of the biggest airship ever made by man scattered over a small church inside Belgium. It was something! He now realized that he was still deep behind the German lines, thirty-five miles deep, to be exact, and the chances of reaching the friendly lines of France seemed dubious at best. The Morane was now in full glide mode, it dawned on him that the best he could hope for was a smooth crash landing somewhere in Western Germany, and a long spell as a prisoner of war. |

|

|

Despite the heavy fog, the unfamiliarity of the terrain, and the lack of any ground light, Reggie landed his plane safely in an open field near a long wooden fence. There was an old barn, but no one emerged to meet him, no German troops were there to take him prisoner. His initial thought was to destroy the Morane, but after a long look at the shot-up plane, he decided to give the Le Rhone a try. Warneford was a better than average mechanic and quickly discovered the cause of the engine malfunction, a ruptured fuel line—possibly caused by the incoming fire he took from the L37—was the main cause of the damage. He searched for what ever he could find to fix the line—reaching deep into his pocket he found his cigarette holder. The wide outer end was perfect for making a temporary repair and the two ends were bound secure with strips from his handkerchief. He proceeded to restart the Le Rhone, which caught-on immediately, thanks in great part, because the engine was still warm. Proceeding to see his fuel gage, Warneford knew he had enough fuel to reach Furnes or even Dunkirk. Immediately he took off fearing that the Germans would soon learn of his location, and after a brief climb, he leveled off the Morane.

As he approached the coast of France, he again ran into a deep fog, so he cruised up and down until he found a crest . When Reggie emerged from the fog, he was disoriented and had no idea where he was. He located a small field below and proceeded rapidly to land his aircraft on it. After landing, the ground crew, all British with a couple of American volunteers, enthusiastically greeted him. They told him that he was at Cape Gris-Nez, a full ten miles south of Calais. He telephoned his home base at Dunkirk and briefly told his commander about his adventure on the skies over Ghent. Commander Longmore told him to sit out the weather and come back to base when it cleared. By the time Warneford returned to his base, the news of the downed Zeppelin in Ghent had traveled far. His name was ringing from one end of the Empire to the other. Within just thirty-six hours of his exploits, Reggie was awarded the prestigious Victory Cross by King George V. The French government follow suit and awarded him the Legion of Honor. |

|

| Reginald Alexander John Warneford was killed in an airplane accident only ten days after he downed the L37. He is buried at Brompton Cemetery, London. |

|

Unfortunately, Flight Sub-lieutenant Reggie Warneford would have only ten more days to bask in his new found glory. He was sent to Paris to receive another decoration on June 17th. After the ceremony was finished, he was ordered to Buc to pick-up a brand new Farman Biplane. There, he took an American reporter, who wanted to write a piece about Reggie’s adventure, along for the ride on the biplane. Shortly after take-off, the Farman began experiencing pitch troubles and went into a complete spin, throwing both the reporter and Warneford out of the cockpit. They were killed immediately. Years after his death, the story of Warneford's extraordinary feat could be found in all the local newspapers as well as countless stories, told all over the battle front.

The author Paul Colon is a freelance writer who resides in San Juan Puerto Rico. rcolonfrias@yahoo.com |

Return To Articles Index.

© The Aviation History On-Line Museum.

All rights reserved.

July 6,2007.