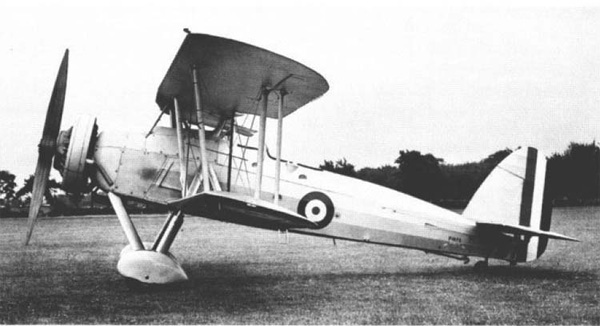

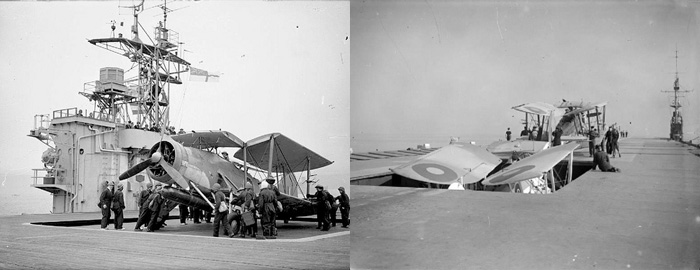

The wings folded back to save space aboard aircraft carriers.

|

Armament was more akin to that of a World War I fighter with only a single forward firing Vickers machine and a single flexible Lewis machine gun for the rear gunner. The only thing that made it a formidable weapon was the 1,670 lb. (757 kg) torpedo that it carried. If it could survive being shot down, the sting of its torpedo was devastating. Improvements to the Mk II introduced in 1943 featured an all-new lower metal constructed wing, allowing it to be equipped with up to eight 60 lb. (27 kg) RP-3 series rockets (four to a side), mounted under the wing. By the war’s end, it would be armed with only a single 1,500 lb. (680 kg) mine for anti-submarine duty making it very effective against U-boats.

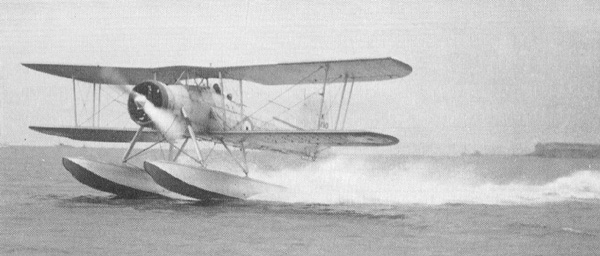

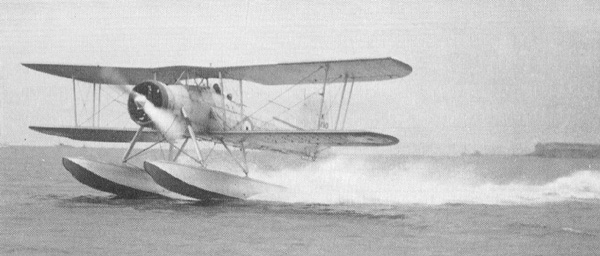

A TSR II equipped with twin floats.

The Swordfish had a conventional tail unit with single tail wheel. The crew consisted of three that included a pilot, observer and radio operator/gunner. Due to the large size of its wings and tail, drag was high and performance was considerably poor when compared to the conventional fighters at the time. It had a top speed of only 138 mph (222 km/h) and a lackluster rate-of-climb of 1,220 ft./min (6.2 m/sec).

The Swordfish in Action

The first fighting mission that the Swordfish engaged in was during the Norwegian campaign in April 1940. During the Battle of Narvik, a Swordfish launch by catapult off the HMS Warspite, served as a spotter for the ships guns as well as other ships. This action led to the destruction of seven enemy destroyers. A Swordfish, piloted by Petty Officer F.C. Rice, also sank the U-64 and finished off one of the destroyers in another attack. This was the first U-Boat to be destroyed by the FAA during World War II.2

In the next few weeks, Swordfish were constantly attacking targets in the Narvik area that included enemy ships, enemy aircraft parked on frozen lakes as well as performing submarine patrols and reconnaissance missions. Weather conditions were extremely harsh and pilots were known to land on snowdrifts or frozen fiords when visibility was reduced to only a few yards above the surface. On one occasion, the landing gear of a Swordfish, from the carrier HMS Furious, was seriously damaged by flak after a low-level attack on German destroyers. Although he was one of the first to arrive back from the mission, the pilot circled for an hour until all the other Swordfish had landed, rather than risk blocking other aircraft from landing.

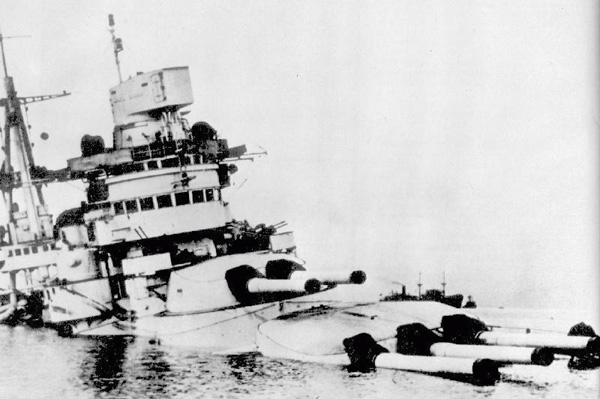

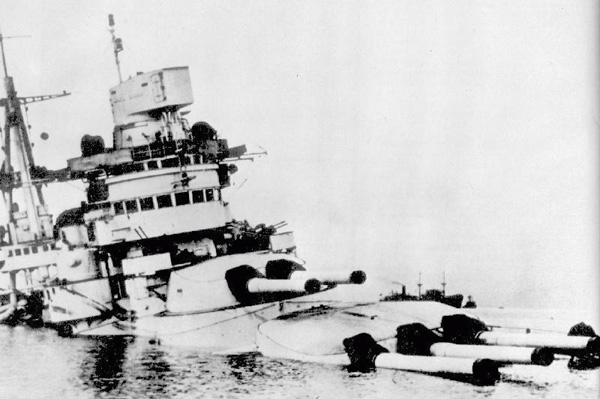

The German destroyer Bernd von Arnim, scuttled during the battle of Narvik.

In the Mediterranean on the island of Malta, Swordfish of the No. 830 Squadron operated from a base at Hal Far. An island fortress, Malta is located sixty miles south of Sicily and had been held by the British since 1800. Situated midway between Gibraltar and Alexandria, it served as a refuge and refueling station for military and merchant shipping. For the British, Malta was the key to the Mediterranean.

Although Swordfish numbered no more than 27 aircraft in Malta, they sank an average 50,000 tons (50,800 MT) of shipping every month. During one month, they sank a record 98,000 tons (99,572 MT). Swordfish attacked enemy convoys at night although they were not equipped with night instrumentation. The risky night missions were necessary to avoid German fighters which encircled the island of Malta by day. On June 30, 1940, Swordfish completed a raid attacking oil installations at Augusta in Sicily.

In July of 1940, after the fall of France in June, Swordfish were used for the destruction of the French fleet at Oran. Aircraft of Nos. 810 and 820 squadrons, flying in three groups of four, attacked and severely damaged the battle-cruiser Dunkerque. This demonstrated that torpedo-bombers could be successfully used to effectively attack capital ships at harbor.

On August 22, 1940, three Swordfish of No. 813 Squadron sank four German ships in Bomba Bay, Libya. Reconnaissance reported that a submarine and depot ship were operating from the bay, but when they arrived there was another submarine and destroyer in view. One submarine was already under way and the lead aircraft, piloted by Captain Oliver Patch R. M., dropped his torpedo from 300 yards (275 m) which hit the sub amidships. The submarine exploded and when the smoke cleared, only the stern of the sub was visible. With his torpedo launched, Patch circled back to base while the other two planes launched their attack. They came upon three ships moored abreast of each other that included the depot ship, an additional submarine and a destroyer moored between both ships. One Swordfish, piloted by Lt. J. W. G. Wellham, attacked the depot ship on the starboard beam and Lt. N. A. F. Cheesman dropped his torpedo from 350 yards (320 m) towards the flank of the submarine. The submarine exploded first, setting fire to the adjacent destroyer and then the depot ship was hit, setting it ablaze. Both Swordfish headed out to sea, and as Lt. Cheesman was circling the Italian airfield at Gazala, there was a tremendous explosion in the bay. The magazine of the depot ship had exploded and all three ships were engulfed in a cloud of smoke, fire and steam. When the three airmen returned to base, Operations was somewhat skeptical that four ships were sank with only three torpedoes, but the claim was confirmed with photographic evidence from a reconnaissance Bristol Blenheim.3

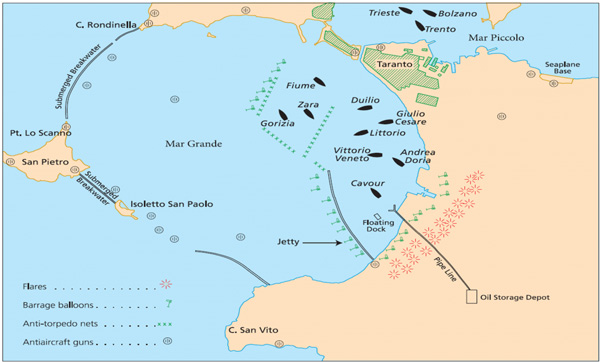

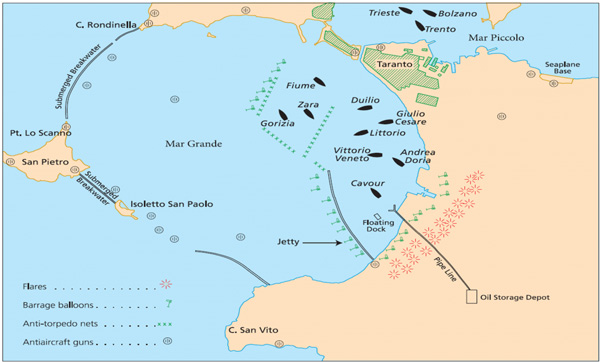

The Attack of Taranto

The greatest success of the Swordfish was a night-attack from HMS Illustrious against the Italian fleet at Taranto in November 1940. Twenty Swordfish were involved and dealt a crippling blow to the fleet. The battle plans for the Taranto attack were originally devised in 1935. The plans were ordered by Admiral Dudley Pound after Italy had invaded Abyssinia. In 1938, the plan was updated by Captain L. St. George Lyster and thoroughly tested and finally presented in 1940. A moonlit night-attack was seen as the best option to maintain an element-of-surprise, and intensive night-flying training was ordered for the crews. Accurate photo reconnaissance was also a requirement for the mission. The photos would show not only that ships were in port, but the actual positions of the ships as well.4

The HMS Eagle was intended to be part of the attack, but due to a malfunctioning fuel system, from near misses of a prior attack on July 11th, she could not participate and five aircraft and eight crews of the Nos. 813 and 824 Squadrons were transferred to the Illustrious.

In June of 1940, Italy’s main battle fleet consisted of six battleships—two of the new Littorio class and four of the recently constructed Cavour and Duilio class. Approximately five cruisers and twenty destroyers were also based at Taranto. On the night of the attack, aerial reconnaissance showed five battleships in the outer harbor, and three cruisers protected by submarine nets and barrage balloons. A sixth battleship was seen entering the harbor later on the same day.

The attack was carried out in two waves. The Illustrious was positioned 170 miles (275 km) from Taranto and twelve aircraft from Nos. 813, 815, 819 and 824 Squadrons were launched at 20:35 hours. Only six aircraft carried torpedoes—four carried bombs and two carried both bombs and flares. No gunners were onboard—instead extra fuel was carried in place of the gunners. The first wave was led by Lieutenant Commander K. Williamson.

The attack began by dropping a line of flares from 7,500 ft. (2,285 m) and these two aircraft dove through heavy flak and dropped their bombs on an oil storage depot and set it ablaze. As the flares lit up the harbor, the attack was led by Williamson, but his plane was hit by flak and he was forced to ditch. A second aircraft attacked a Cavour-class ship from 700 yards (640 m) and scored a hit. Other aircraft attacked the same ship but scored no hits. Other planes concentrated on two Littorios and one ship received several hits. Of the first wave, all aircraft returned with the exception of Williamson.

A second wave lifted off from the Illustrious at 21:23 hours led by Lieutenant Commander J. W. Hale. Five aircraft were armed with torpedoes, two with bombs and two with bombs and flares. One aircraft left 20 minutes late after being damaged while taxiing on the flight deck. One aircraft aborted the mission due to a malfunction, but the remaining eight aircraft reached their target. The attack procedure was repeated as the first with two aircraft dropping flares and attacking the oil depot. The other aircraft concentrated on two Littorios. One aircraft came in so low that its landing gear hit the water sending up a tremendous spray, but luckily he was able to recover. Only one aircraft failed to return from the second wave.

The Conte di Cavour.

Aerial reconnaissance two days later showed that the Cavour-class battleship Conte di Cavour was sunk; one Duilio-class battleship was heavily damaged; one Littorio was badly damaged, one Trento-class and one Bolzano-class cruiser were severely damaged, two destroyers were damaged; and two auxiliary vessels were sunk. Italy’s serviceable battleships had been reduced from six to two—only Vittorio Veneto and Giulio Cesare had escaped damage.

The lopsided victory was achieved at a cost of only two Swordfish. Success of the mission was due to accurate photographic reconnaissance, almost up to the last hour, and the ability to carry out a surprise attack. This same type of attack would be repeated a year later except on a much larger scale. However, it wouldn’t be the British attacking this time, it would be an attack carried out by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the American fleet, anchored at Pearl Harbor.

|

The Bismarck under attack.

|

|

The Sinking of the Bismarck

On May 26, 1941, a Swordfish made a critical strike that led to the sinking of the Bismarck by disabling its rudder. The initial attack was followed 13 hours later by a bombardment of the Royal Navy which finally critically damaged the ship. Although heavily damaged, the Bismarck failed to sink and the ship was scuttled by the crew.

It wasn’t until the year 2000 that John Moffat would learn that it was his torpedo that crippled the Bismarck. He was piloting one of three Swordfish that was operating from the HMS Ark Royal. John's mission was to avenge the loss of the HMS Hood, with 1,416 lives lost, afer being sunk by the Bismarck.

On that day, the Ark Royal was pitching in 60 ft. waves, water was running over the decks and the wind was blowing at 70 or 80 mph. After the planes were brought up from the hangar deck, it took ten men to lock each wing into place. In howling winds and as the deck pitched up and down, deck hands cranked inertia starters to start each plane's engine.

After takeoff, John climbed to 6,000 feet to get above a thick cloud and when he got close to the Bismarck, all hell broke loose from the ship’s fire. He dove to down to attack and saw an enormous ship in front of him. John described the action in his book, “I Sank the Bismarck”, published in 2009.

|

|

“I must have been under 2,000 yards when I was about to launch the torpedo at the bow, but as I was about to press the button I heard in my ear "Not now, not now!" I turned round and saw the navigator leaning right out of the plane with his backside in the air. Then I realized what he was doing—he was looking at the sea because if I had let the torpedo go and it had hit a wave it could have gone anywhere. I had to put it in a trough. Then I heard him say, "Let it go!" and I pressed the button. Then I heard him say, "We've got a runner," and I got out of there.” Moffat pulled up his Swordfish before the torpedo hit and wasn’t able to see if he made a strike. The following morning he flew to the ship for a second attack, but it wasn’t necessary. He watched the Bismarck as it rolled over after being under siege from the Royal Navy. He witnessed hundreds of German sailors leaping into the water as she started to sink. John said, “I didn't dare look any further, I just got back to the Ark Royal and I thought, 'There but for the grace of God go I.'”

|

|

After the battle, HMS Dorsetshire and Maori attempted to rescue survivors, but a U-boat alarm caused them to leave the area. Of the 2,200-man crew, only 115 German sailors were rescued at the end of the battle.

All six Swordfish were shot down in the Channel Dash.

The Channel Dash

On February 11, 1942, its shortcomings finally became apparent during the Channel Dash, when German battleships escaped a British blockade of the port city of Brest. During the attempt to torpedo the German battleships, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen, all six Swordfish, led by Lieutenant Commander Eugene Esmonde, were shot down by German fighters. The German air interception was a highly organized attack that was planned by none other than the famous Luftwaffe General, Adolf Galland. Although several Swordfish started their runs and dropped their torpedoes, no torpedo found a target. Of the eighteen Swordfish crewman, only five survived to be pulled from the Channel. Commander Esmonde was not among them.5 After this tragedy, it was never used as a torpedo bomber again. They were easy targets for fighter aircraft, but they were most vulnerable during long torpedo runs. It was then relegated to performing anti-submarine missions and in the training role. However, overall losses for the Swordfish were relatively light, because it was primarily used where it wouldn’t be opposed by land-fighters.

In the anti-submarine role, the Swordfish was very successful patrolling at night usually 90 miles (145 km) or 25 miles (40 km) ahead of convoys. Targets were located with ASV radar and visually sighted by dropping flares. In September 1944, a Swordfish from the HMS Vindex sank four U-boats in one voyage. In total, the Swordfish accounted for the destruction of 22.5 U-boats. The last Swordfish squadron was No.836, which was disbanded on May 21, 1945, but the last operational mission was flown on June 28th.

Conclusion

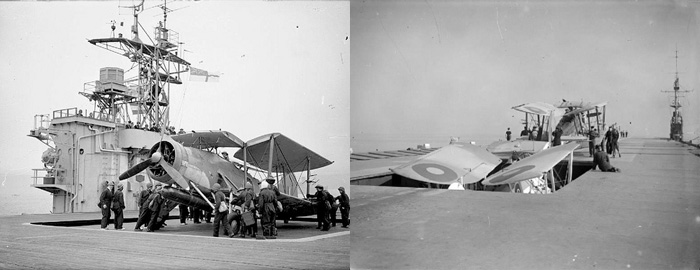

Despite all of its shortcomings, it was remarkably easy to fly and land on carriers, which was particularly useful when landing on short deck escort carriers. It could make remarkably tight turns and steep dives low to the surface, and then make an abrupt recovery. Its takeoff and landing speeds were so low that, unlike most carrier-based aircraft, it did not require the carrier to be steaming into the wind. And if the wind was right, a Swordfish could be flown from a carrier while at anchor. A Swordfish could actually be pulled off the deck and put into a climbing turn at 55 knots (100 km/h).6

To facilitate takeoffs with a heavily laden Swordfish, Rocket Assisted Take-Off Gear (RATOG) was installed. This comprised of two solid fuel rockets affixed to either side of the fuselage close to the aircraft’s c.g. which exhausted just aft of the lower wing. On takeoff, the tail was raised as early as possible, the rockets would then be fired and the plane brought to an almost three point position just before reaching the end of the deck. No change of trim was required after the rockets were fired. Without rockets, the normal takeoff run was 650 ft. (200 m) with a takeoff weight of 9,000 lbs. (4,082 kg) into a 12 knot (22 km/h) headwind. With rockets under the same conditions, the takeoff run was reduced to 270 ft. (82 m).7

If the Swordfish could survive being shot down, its torpedo had a powerful sting. However, losses were relatively light since it normally used where it wouldn’t be opposed by land-fighters.

In 1943, the Mk.III, powered by the Bristol Pegasus XXX engine, was introduced featuring ASV radar mounted between the landing gear. The final Swordfish production model became the Mk.IV which was very distinct from earlier offerings in that it featured an enclosed cockpit for the crew of three. However, Mk.IVs were actually retrofitted Mk.IIs and were operated by the Royal Canadian Air Force. It was first powered by 690 hp (515 kW) Bristol Pegasus IIIM.3 and then upgraded to a 750 hp (560 kW) Bristol XXX.

Operators included the RAF, RNFAA, Canada, Netherlands, South Africa, and Spain. The pre-war British squadrons were Nos. 810, 811, 812, 813, 821, 823, 824, and 833 on the carriers Ark Royal, Courageous, Eagle and Furious. Britain operated some 26 squadrons of Swordfish in total.8

The Fairey Albacore biplane was introduced during the early 1940's to replace the Swordfish, but the Swordfish outlived the Albacore to fight on until the war's end. It was finally replaced by the much improved Fairey Barracuda monoplane.

Fairey ceased production of the Swordfish in early 1940 in order to concentrate on the Albacore. Production was continued by the Blackburn Aircraft Company in Sherburn and produced 1,699 aircraft. These aircraft were sometimes dubbed "Blackfish" due to their Blackburn factory origins. Production of the Swordfish continued until August 18, 1944 and it remained in service until VE day on May 8, 1945. The total production of the Swordfish amounted to 2,392 aircraft. The Mark II was the most produced version of which 1,080 were made. The number of versions produced were as follows: 989 Mk.Is, 1,080 Mk.IIs, and 327 Mk.IIIs. Mk IVs were actually retrofitted Mk IIs. There are nine surviving Swordfish and four are currently airworthy.

|

|

Specifications: |

| Fairey Swordfish |

| Dimensions: |

| S.9/30 |

Mk.1 |

| Wing span: |

46 ft 0 in (14.02 m) |

45 ft 6 in (13.87 m) |

| Length: |

34 ft 1 in (10.39 m) |

35 ft 8 in (10.87 m) |

| Height: |

14 ft 0 in (4.27 m) |

12 ft 4 in (3.76 m) |

| |

Weights: |

| Empty: |

|

4,195 lb (1,905 kg) |

|---|

| Loaded Weight: |

5,740 lb (2,604 kg) |

7,720 lb (3,505 kg) |

|---|

| |

Performance: |

| Maximum Speed: |

147 mph (237 km/h) |

154 mph (246 km/h) |

|---|

| Cruise Speed: |

|

131 mph (210 km/h) |

|---|

| Service Ceiling: |

|

19,250 ft (5,870 m) |

|---|

| Range: |

|

522 miles (840 km) |

|---|

| Powerplant: |

One 525 hp (390 kW)

Rolls-Royce Kestrel IIMS engine. |

One 690 hp (510 kW)

Bristol Pegasus IIIM.3 radial engine. |

| Armament: |

One fixed forward firing .303 caliber

Vickers machine gun and

one rear cockpit flexible .303 caliber

Lewis machine gun. |

One fixed forward firing .303 caliber

Vickers machine gun and

one rear cockpit flexible .303 caliber

Lewis machine gun. |

Endnotes:

1. H. A. Taylor. Fairey Aircraft since 1915. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1974. 232.

2. Owen Thetford. British Naval Aircraft since 1912. London: Putnam and Company Ltd., 1978. 136.

3. Ian G. Scott. Aircraft in Profile, Volume 10. The Fairey Swordfish Mks. I-IV. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, 1971. 34.

4. Lt. Col. Angelo N. Caravaggio. The Attack at Taranto. Newport, Rhode Island: Naval War College Review, 2006, Vol.59, No. 3. 108-109.

5. Donald L. Caldwell. JG 26, Top Guns of the Luftwaffe. New York: Ballantine Books, 1991. 104-108.

6. Terence Horsley. Find, Fix and Strike: The Work of the Fleet Air Arm. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1943.

7. Eric Brown. Wings of the Navy, Flying Allied Carrier Aircraft of World War Two. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1987. 17-18.

8. Kenneth Munson. The Pocket Encyclopedia of World Aircraft in Color. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1970. 109.

|

Return to Aircraft Index

©Larry Dwyer. The Aviation History Online Museum.

All rights reserved.

Created May 26, 2015. Updated January 2, 2023.

|