|

Grumman F6F Hellcat by Earl Swinhart |

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Crash landing of F6F on flight deck of USS ENTERPRISE while enroute to attack Makin Island. Lieutenant Walter Chewning, catapult officer, clambering up the side of the plane to assist pilot, Ens. Byron Johnson, from the flaming cockpit. Many US Navy pilots had good cause to refer to the Hellcat as the "Aluminum Tank". With its six Browning .50 caliber machine guns, it could spit out a veritable hail of destruction which no Japanese adversary could hope to survive. After the war, Japanese pilots related their fear and dread each time they were engaged by the Hellcat. And, on the other side of the coin, the Hellcat could absorb unbelievable punishment and still bring the pilot back to his ship. Pilots tell of "mostly holes where the airplane used to be" and "more air was going through it than around it". One Hellcat had been burning for a hundred miles before landing on its carrier. Top Navy ace, David McCampbell told of watching the piston and connection rod "popping in and out" of the mangled Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engine as he struggled to fly the pieces of his Hellcat back to the carrier. The Grumman Company itself was often referred to as the "Grumman Iron Works".

On board the USS Saratoga (CV-3). A ground man signals to the pilot of the F6F.

In the spring of 1941, the Navy was looking to replace the Grumman F4F Wildcat in light of new developments in the field of aeronautics, and the worsening military situation both in Asia and in Europe. On June 30, 1941 the Navy ordered two prototypes, the XF6F-1 and XF6F-2. They were to have the Wright R-2600-16 engine, producing 1,700 horsepower, on the -1 and a turbo-charged Wright 2600-16 on the -2. Immediately after the first flight of the XF6F-1 on June 26, 1942, the aircraft was redesignated the XF6F-3 and fitted with the new 2,000 hp Pratt & Whitney R-2800-10 engine, which had just become available. Up until the time of the first flights of the XF6F-1, very little reliable information was available on the Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero other than through reports with encounters with the Zero. It was fast, agile and shot down an alarming number of Allied aircraft. As happened on many occasions during WWII, Lady Luck was about to change all that. Shortly after the first flight of the XF6F-1, a curious incident was occurring 2,500 miles (4,023 km) away on a small island known as "Akutan" in the Aleutian chain which would have a devastating effect on the supremacy of the Zero.

Dynamic static. The motion of its props causes an "aura" to form around this F6F on the USS YORKTOWN. The rapid change of pressure and drop in temperature create condensation. Rotating with blades, the halo moves aft, giving depth and perspective.

A Navy PBY, making a routine patrol, happened to pass over tiny Akutan Island and one of the observers aboard happened to notice a dark speck on the tundra below which appeared out of place. The pilot took the "Catalina" down to have a closer look. The speck turned out to be a Japanese aircraft, and even though it was upside down, it was almost immediately identified as a Zero. The radioman sent the coordinates and within hours a Navy recovery team was on the way to investigate. On arrival, the recovery team found the dead pilot, Flight Petty Officer Tadayoshi Koga still hanging in his seat harness. Koga had had engine problems and tried to land the plane on the flat tundra of the small island with the wheels down. The wheels dug in and flipped the Zero on its back, snapping F.P.O. Koga’s neck in the process. The Zero was almost undamaged, even the engine looked to be in good shape aside from a broken oil line. The Zero was dismantled and shipped directly to the Grumman Aircraft factory in California where it was reassembled and flown. The information gleaned from this fortunate confirmed the increase in power on the Hellcat. It was found that the XF6F-1 would have been marginally slower than the Zero if it was powered with the Wright R-2600. The Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engine boosted the Hellcats top speed to 375 mph (604 km/h), 29 mph (47 k./h) faster than the Zero. There are two versions of how the “Akutan Zero” affected the selection of engines for the Hellcat. The old version saying the engine was upgraded, because of the Akutan Zero, has been declared a myth. The Akutan Zero did provide very important intelligence on its performance and this information was used to make improvements on the F4F Wildcat, but only so much could be done, because Wildcat production was in full swing at this time. But some of the intelligence was used for the Hellcat, which was just about to enter production.1 However, some historians feel that the Akutan Zero that the Akutan Zero had nothing to do with the development of the Hellcat since it flew only two weeks before the first flight of the F6F-3 production version, in October 1942.2 |

|

With certainty the following can be said:

• Two XF6F-1 prototypes were ordered on June 30, 1941. |

|

The decision to change the XF6F-2 Wright engine for the R-2800 was 23 days before the first flight of the XF6F-1, and this was more than a month before the Akutan Zero was even sighted. Although the Akutan Zero did not fly until September, some intelligence had to be divulged to Grumman before the first flight of the XF6F-3. The Akutan Zero may not have figured into the selection of engines, but the information certainly would have aided in the design of the production version F6F-3.

A Hellcat goes down the deck for take-off on the USS Lexington (CV-16).

In terms of size, the Hellcat was the second largest single engine

fighter of the war, being ever-so-slightly smaller than the

P-47 "Thunderbolt".

At first glance, the F6F appeared too big to

operate safely from a carrier. But The Grumman Iron Works had a great

deal of expertise in building carrier aircraft. The US Navy wanted a

much faster plane carrying heavier loads over far greater distances.

The only way to achieve all three goals was the obvious way; design a

larger aircraft. There was room for a more powerful engine, room for

more armament and for extra fuel.

Navy crewmen aboard the USS Monterey (CVL-26) bringing an F6F to the flight

deck on an elevator.

Also produced were models with a suffix "N" after the dash number. These were night fighters with an APS-6 radar mounted on the starboard wing near the tip. The first production batch of dash three’s were assigned to VF-9 aboard the carrier Essex. The first combat sorties were flown by VF9 and by VF-5 aboard the Yorktown on August 31, 1943 against Japanese targets on Marcus Island (Minami-tori Island) some 700 miles (1,127 km) southeast of Japan. The first real test of the F6F-3 against the Zero came a few months later in December when a group of about a hundred Hellcats ripped into a like number of Japanese planes of which half were Zeroes. In the ensuing battle, 28 of the Zeroes were "splashed" (destroyed and crashed into the water) for a total loss to the Hellcats of 3 planes.

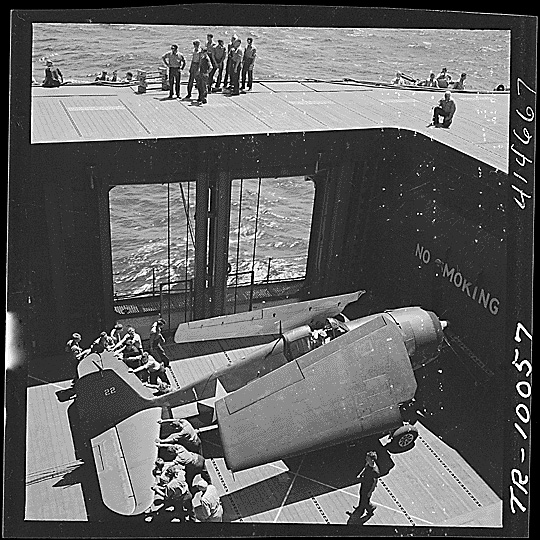

Surrounded by F6F's ordnance, men work on bombs on the hangar deck of

the The engagement which put a final seal of approval on the Hellcat took place over the Philippine Sea on June 19/20, 1944. This incident was officially called the "Battle of the Philippine Sea". To the pilots who fought, it will always be known as "The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot". It began in the early morning of the nineteenth with a few skirmishes over the island of Guam while Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, commanding the Japanese Mobile Fleet of nine fast carriers plus assorted battleships, cruisers and destroyers attempted to find the US Fast Carrier Task Force of the 5th Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Mark Mitscher. Ozawa had nine carriers and 450 planes to Mitschers 15 carriers and 900 aircraft. By 10:00 am on the 19th, the adversaries had located each other and the Turkey Shoot was about to reach its peak. Admiral Ozawa launched about 70 aircraft of various types including 28 Zeroes plus a number of fighter-bombers and torpedo planes. When they were still 150 miles away they were picked up on radar. Admiral Mitscher turned his carriers into the wind for launch. These seventy Japanese aircraft were swarmed by hundreds of Hellcats from the Carrier Task Force. Only 24 of the Japanese craft survived. Of the 24, a single fighter-bomber managed to inflict casualties and slight damage to the battleship South Dakota. Ozawa sent a second wave of aircraft toward the 5th Fleet and another debacle ensued; ninety-eight of 128 aircraft were splashed before reaching the ships. He launched two more strikes with similar results. In all, Ozawa lost almost 350 aircraft the first day of the battle (virtually all were downed by Hellcats), while accomplishing almost nothing. The US carriers lost 30 planes.

Pilots leaning across F6F on board the USS Lexington (CV-16) after shooting down 17 out of 20 Japanese planes heading for Tarawa. L - R: Ens. William J. Seyfferle; Ltjg. Alfred L. Frendberg; Lcdr. Paul D. Buie; Ens. John W. Bartol; Ltjg. Dean D. Whitmore; Ltjg. Francis M. Fleming; Ltjg. Eugene R. Hanks; Ens. E.J. Rucinski; Ltjg. R.G. Johnson and Ltjg. Sven Rolfsen.

In addition to the aircraft destroyed, Ozawa lost the carriers Taiho (the newest and largest of Japans carriers, thought to be unsinkable) and the veteran carrier Shokaku. During the early evening of the 19th, Ozawa began withdrawing from the battle but was pursued by Mitscher all that night and all the next day, further decimating Ozawas carrier aircraft. After the Turkey Shoot, the Japanese could no longer establish or maintain air superiority over their naval objectives due to their loss of carrier aircraft and experienced pilots. Their vaunted A6M "Zero" was no longer invincible. They had gained a great respect for "The Grumman Iron Works" and its F6F "Hellcat"! |

| Specifications: | |

|---|---|

| Grumman F6F-5 Hellcat | |

| Dimensions: | |

| Wing span: | 42 ft 10 in (13.05 m) |

| Length: | 33 ft 10 in (10.31 m) |

| Height: | 14 ft 5 in (4.39 m) |

| Wing Area: | 334 sq ft (31 sq m) |

| Weights: | |

| Empty: | 9,060 lbs (4,110 kg) |

| Normal Gross: | 12,598 lbs (5,714 kg) |

| Maximum Gross: | 15,413 lbs (6,991 kg) |

| Performance: | |

| Maximum Speed: | 380 mph (612 km/hr) @ 23,400 ft (7,132 m) |

| Cruising Speed: | 200 mph (322 km/hr) |

| Landing Speed: | 88 mph (142 km/hr) |

| Service Ceiling: | 37,300 ft (11,369 m) |

| Combat Range: | 945 mi (1,521 km) |

| Maximum Range: | 1,530 mi (2,462 km) |

| Powerplant: | |

| Pratt & Whitney R-2800-10W "Double Wasp" Air Cooled Radial 2,000 hp (1,492 Kw) Take-Off - 1,975 hp (1,473.9 Kw) @16,900 ft (5,151 m) | |

| Armament: | |

| Six .50 caliber (12.7 mm) Browning M-2 machine guns with 2,400 rounds mounted in the wings. Later models could substitute two 20 mm guns for the two inboard .50 calibers. | |

Endnotes:

|

1. Richard Thruelsen. The Grumman Story. New York: Praeger Publishers, Inc., 1976. 167. 2. Stephen Wilkinson. The Goldilocks Fighter. Aviation History, July 2014. 24. |

© Earl Swinhart. The Aviation History Online Museum.

All rights reserved.

Created October 30, 2000. Updated February 13, 2023.