|

|

Boeing P-26 Peashooter |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

||

|

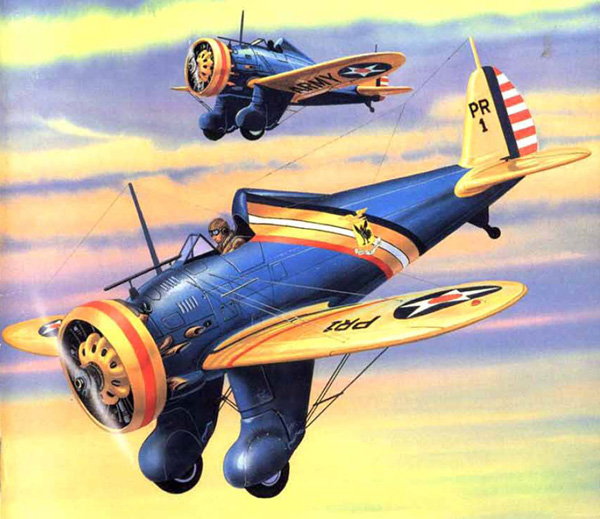

Boeing P-26C of the 19th Pursuit Squadron, 18th Pursuit Group, Wheeler Field, Hawaii.

| ||

| After the Boeing Airplane Company completed the first B-9 Bomber for the US Army Air Corps (USAAC) on April 29, 1931, the twin-engine behemoth proved to be faster than any other bomber in the world. It was so fast that existing American fighters had trouble intercepting it. The B-9 had a maximum speed of 188 mph (302 km/hr), while the Boeing P-12E pursuit fighter had a speed of 189 mph (304 km/hr) and the Curtiss P-6E, still to be delivered, could do 197 mph (317 km/hr) only under ideal conditions. |

| With the development of the B-9, some observers felt that the day of the fighter was at an end, but Boeing engineers thought they could produce a small fighter that would be fast enough to overtake their own B-9 Bomber and combat it successfully. Their answer was the Boeing P-26 Pursuit Fighter. Design work on the P-26 was undertaken during 1931 and production began the following January. Three experimental models designated the XP-936 (Model 248) were built at company expense. The first flight was on March 20, 1932.1 |

|

The P-26A (Model 266) was the first all-metal, low-wing fighter to be put into production in the United States. It was another progression up from the

Boeing P-12

of which the aft fuselage was all-metal, semi-monocoque construction.

The P-26 was also the last open-cockpit fighter built for the USAAC, the last with a fixed landing gear, and the last with externally braced wings. Even more, it was the last fighter built on the theory that fighters had to be kept light and small for better maneuverability. However, it was still conservative in design and was considered an interim fighter, between the biplane era and monoplanes. It would take more time for the latest NACA developments that were used in the Boeing B-9 and

Monomail to be incorporated in American built fighter designs.

During testing at the 20 foot (6 meter) NACA wind tunnel at Langley Virginia, built in 1927, engineers experimenting with a Sperry Messenger, discovered that drag could be decreased by 40% with the installation of a retractable landing gear. Another experiment with a Curtiss Hawk in 1927 showed the advantages of streamlining with the NACA engine cowling. Airspeed in this case increased from 118 to 137 mph (190-220 km/hr)—an increase of 16%. With the release of this data, aircraft manufacturers rushed to create aircraft with retractable landing gear and install the NACA cowling. Although the P-26 incorporated the NACA engine cowling, retractable landing gear were still prone to malfunctioning at this time. Besides having a weight penalty, details for a strong retractable landing gear for fighter aircraft that would fit into the wing and fuselage, while maintaining structural integrity was still in the process of being worked out. 2 Boeing had already built cantilever winged aircraft with retractable landing gear, so the P-26 seemed like a step backward.

The USAAC was not fully convinced that the cantilever wings would withstand the rigorous flight maneuvers expected from a fighter, so wire bracing was added. This would induce drag, but not as much as wing struts. And although it was a 200 mph (322 km/hr) aircraft, it still had an open cockpit. Pilots at the time, still preferred open cockpits mostly for the feel of flying and for better visibility—early versions often caused optical distortion and instrumentation was not always reliable. Its clean lines and short wings gave it a high speed, but at a cost of ease of handling that experienced pilots had been accustomed to on biplanes. The P-12 and P-26 were both powered by the same 500 hp (370 kW) R-1340-27 Wasp engine, but the P-26 was 20 percent faster and had a range of 375 miles (600 km)—75 miles (120 km) farther than the P-12. The rate of climb for the P-26 was 476 ft/min (2.42 m/sec) higher than that of the P-12. However, because of the P-26’s higher wing loading, it had a ceiling 800 ft less (240 m) than the P-12. Most alarming though was the landing speed of 82 mph (132 km/hr)—17 mph (27 km/hr) faster than the P-12—but this was corrected to a more acceptable 73 mph (117 km/hr) after flaps were retrofitted to all P-26s.3 Another modification came after a crash with one of the prototypes in which the plane tipped over. Although damage was light, the pilot broke his neck. Pilots were protected in biplanes by the upper wing in this type of accident. To protect the pilot, the headrest was raised eight inches (20 cm) and was reinforced with a roll-bar similar to today’s race cars. This gave the P-26 its characteristic humpback look. The next model was the P-26B (Model 266A) with an upgraded 600 hp (465 kW) Pratt & Whitney R-1340-33 fuel injected engine, but these engines were in short supply and only two were built. The next model, the P-26C, had provisions for both the carbureted and fuel injected engine, and as the upgraded engines became available, the Cs were retrofitted as Bs, with fuel injected engines. Despite its shortcomings, the USAAC ordered 111 P-26As on January 11, 1933, later increasing this to 136—making it the largest single contract for aircraft issued since the Boeing MB-3A order of 1921. Deliveries to service squadrons began in December 1933 and the last P-26C, was rolled off the assembly line in 1936. Externally, all P-26 models were similar with the majority of changes being internal.

A Boeing P-26 undergoing wind tunnel tests in 1934 at the world’s first full-scale wind tunnel, at Langley Field, Virginia. The wind tunnel was 60 feet wide by 30 feet high and limited to about 125 mph. In an effort to promote itself in lean times during the Depression, the Army Air Corps painted its new fighters in brilliant colors with the most flamboyant group being the 17th Pursuit Group at March Field in southern California. This consisted of the 34th, 73rd and 95th pursuit squadrons. The airplane was named the Peashooter for its gun blast tubes, but not for complimentary reasons. Its armament was two synchronized 0.30 caliber, or one 0.30 caliber and one 0.50 caliber machine guns mounted in the cockpit floor and it could carry 200 lb. of bombs between the landing gear. It wouldn’t take long to find out that the armament would prove to be totally inadequate.The P-26 became outmoded by the Martin B-10 with its enclosed cockpit and retractable landing gear with a top airspeed of 234 mph (377 km/hr) and with the appearance of the Seversky P-35 and Curtiss P-36. It quickly became outclassed with the introduction of the Hawker Hurricane, Messerschmitt Bf 109, Mitsubishi Zero and even the Polikarpov I-16, which made its first flight on December 31, 1933—making the P-26 obsolete almost from the start. However, the P-26 remained in active service for many years and in November 1940, one year before the start of World War II, the Air Corps’ entire fighter strength in the Philippines consisted of only 28 P-26s. Most of these were destroyed in the first Japanese attacks but two of them, flown by Philippine pilots, became the first American pilots to shoot down Japanese airplanes. The 6th Fighter Squadron of the newly constituted Philippine Army Air Corps shot down one Mitsubishi G3M bomber, and at least two and possibly three Zeroes, flying Boeing P-26s. Eleven Model 281s (the export version of the P-26C) were sold to the Chinese Nationalist Air Force in 1936 and these were the first Boeing fighters to have combat experience. On August 20, 1937, eight P-26Cs of the 17th Squadron commanded by Wong Pan-Yang, engaged six G3M2 Japanese bombers as they carried out a raid on Nanking airport and shot down four without suffering a single loss. By the end of 1937, as the P-26s became inoperable, they were replaced with Gloster Gladiators.

A Philippine Army Air Corp P-26s engages a Mitsubishi G3M bomber. One Model 281 was sold to Spain in 1935, but it was considered too costly and Hispano-Suiza obtained a license to build Hawker Furys. The 281 was equipped with Vickers .303 machine guns and fought with the Republicans. During the years 1932-1934, the P-26 set several speed and altitude records. It was never offered to the Navy who did not fly monoplanes until the introduction of the Brewster Buffalo. By 1938, the P-26 was operational only in Hawaii, Panama and the Philippines and was relegated to the training role. In 1942, it was taken out of front-line service by the US Army Air Force (USAAF). (In June 1941, the US Army Air Corps became the US Army Air Force.) Two P-26s were still flying until 1957 with Guatemala's Air Force, having been kept in service since the early 1940s.4 They were replaced by surplus P-51 Mustangs in 1950 and were sent to museums. One aircraft was restored to its colorful prewar USAAC markings and is now on display in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. The other aircraft was sold to the Planes of Fame Museum located in Chino, California. The P-26 was the last fighter aircraft series built by Boeing until recent times. They would concentrate their efforts on the production of larger aircraft which would include famous aircraft such as the B-17 Flying Fortress and a stream of jetliners starting with the Boeing 707 airliner. Boeing would not be involved in the production of fighters again until it acquired McDonnell-Douglas in 1997 which produced the F-15 and in a joint venture with Lockheed-Martin on the F-22. |

| Specifications: | |

|---|---|

| Boeing P-26A (Model 266) | |

| Dimensions: | |

| Wing span: | 27 ft 11 1/2 in (8.50 m) |

| Length: | 23 ft 10 in (7.26 m) |

| Height: | 10 ft 5 in (3.18 m) |

| Weights: | |

| Empty: | 2,196 lb (996 kg) |

| Operational: | 2,955 lb (1,340 kg) |

| Performance: | |

| Maximum Speed: | 234 mph (377 km/h) |

| Service Ceiling: | 27,400 ft (8,352 m) |

| Normal Range: | 375 miles (603 km) |

| Max. Range: | 635 miles (1,022 km) |

| Powerplant: | |

|

One 500 hp (370 kW) Pratt & Whitney Wasp R-1340-27 nine cylinder, air-cooled, single row radial engine. | |

| Armament: | |

|

Two 0.30 caliber machine-guns or one 0.30 caliber and one 0.50 caliber machine-guns, and 200 lb (91 kg.) of bombs. | |

Endnotes:

|

1. Peter M. Bowers. Boeing Aircraft Since 1916. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1968. 188. 2. Roger E. Bilstein. Orders of Magnitude, A History of the NACA and NASA, 1915-1990. Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Management Scientific and Technical Information Division, 1989. Chapter 1. history.nasa.gov/SP-4406/contents.html 3. Robert Guttman. Boeing's Trailblazing P-26 Peashooter. Aviation History. July 1996. 26. 4. Peter M. Bowers. Aircraft in Profile, Volume 1, Number 14. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1965. 9. |

© Larry Dwyer. The Aviation History Online Museum.

All rights reserved.

Created January 8, 1999. Updated March 9, 2014.